ACT/Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan.

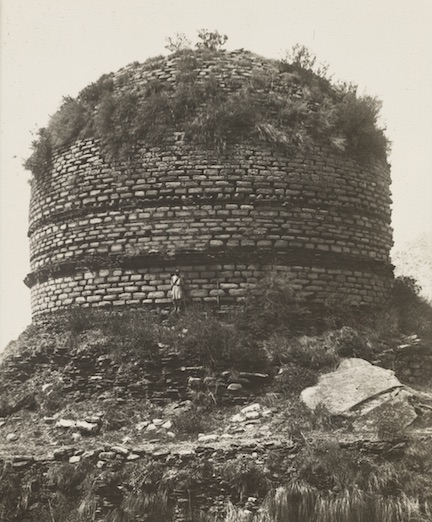

Once rising almost as high as the Pantheon in Rome, the large stupa of Amluk Dara in the Swat valley, Pakistan, is still an imposing building. Yet it is was only one among many such Buddhist structures built in Udyāna, a garden kingdom of the Silk Road.

Owing to its position connecting North India through mountainous Central Asia with the kingdoms and empires beyond, this was a strategic area. It often formed the borders of larger empires, with rulers based in India failing to expand north from here over the mountains and rulers from north of the mountains failing to expand further south from here into the Indian plains. However, one of the early invaders came from much further afield. Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC) fought famous battles here during his central Asian campaigns. His army marched east from Alexander on the Caucasus (Bagram)—the city he had founded in the kingdom of Kapisa—and fought many battles to gain control of the region. Some of these were in the Swat valley and culminated with Alexander’s successful siege of Aornos, a seemingly impregnable steep-sided mountain with a flat top watered by a spring where locals had taken refuge. Identifying the site of this ancient battle has occupied scholars for well over a century, but two places stand out as the most probable candidates. Pir Sar, a mountain rising west of the Indus valley, was selected by the archaeologist Aurel Stein (1862–1943) after his survey of the region in 1926. However, although this is not rejected by all, the consensus now veers toward Mount Ilam, the summit of which is a day’s walk from the Amluk Dara Stupa (Stein 1929; Rienjang 2012; Olivieri 2015).

Photographed in 1926 by Aurel Stein. The British Library Photo 392/30(129).

Legend tells of a serpent king, the Apalala, who lived in a lake high in the peaks of the Hindu Kush. Every year he demanded an annual offering of grain from the people living in the valley of the Swat river, which flowed from the lake. The valley was fertile, hence its name — Udyāna, the garden. But one year the people refused to give the offering and Apalala flooded their lands in revenge. The people duly asked help of Buddha. He came to the valley, converted Apalala and left his footprint on a rock as a sign of his visit.

The footprint survives (now in the local museum), the Swat River still floods, and for many centuries the valley kingdom remained a centre of Buddhism. The location of Amluk Dara and its central stupa was dependent on the landscape. The fecundity of the Swat valley is well captured by the description of the Aurel Stein: “The deep-cut lane along which we travelled was lined with fine hedges showing primrose-like flowers in full bloom, and the trees hanging low with their branches, though still bare of leaves, helped someone to recall Devon lanes. Bluebell-like flowers and other messengers of spring, spread brightness over the little terraced fields.” (Stein 1919: 32-5) And the Italian archaeologists working there since 1956 have noted that “the entire complex blended in with the surrounding nature. From this it drew its charm, importance and beauty—all elements that are believed to have been taken into consideration both in the original plans and subsequent extension.” (Faccenna and Spagnesi 2014: 550)

Gregory Schopen has argued that monasteries were very closely linked to the Indian ideal of a garden containing an arbor or pleasure grove, evidenced by the shared lexicon in the first century AD. He writes that “Buddhist monks . . . attempted to assimilate their establishments to the garden, or actually saw them as belonging to that cultural category.” (Schopen 2006: 489). The framing of views from within the garden or monastery was an important element in its siting, a point noted by many later travelers. So Stein writes of another site in the Lower Swat that it “proved a pleasing example of the care in which these old Buddhist monks knew how to select sacred spots and place their monastic establishments by them. A glorious view down the fertile valley to Thāna, picturesque rocky spurs around, clumps of firs and cedars higher up, and the rare boon of a spring close by—all combined to give charm to the spot. Even those who do not seek future bliss in Nirvāṇa could fully enjoy it.” (Stein 1929: 17-18). Rock-cut or other seats were often placed at points giving a particular view.

During its heyday, monks and merchants carried news of Udyāna’s Buddhist sights and temples along the Silk Road to China and the mountain valley became part of the itinerary for pilgrim monks en route to India. The first to leave a record was Faxian, who arrived in about 403. He stayed for several months visiting the Buddha footprint along with the rock on which he dried his clothes, and the place where he converted ‘the wicked serpent.’ He noted that there were 400 Buddhist monasteries.

Other pilgrims followed, including Xuanzang in 630 and the Korean monk, Hyecho, around 727. By their time Buddhism was in decline in the plains below Swat, but the valley provided an enclave. Indeed, recent archaeological work by Dr Luca Olivieri and his colleagues of the Italian Archaeological Mission has shown that rebuilding of Buddhist shrines and temples continued into the tenth centuries, long after Buddhism had disappeared in its Indian homeland.

Recent excavations. ACT/Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan.

This is an edited extract from my forthcoming book, Silk, Slaves and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road (University of California Press, March 2018). Chapter 4 tells the story of Amluk Dara stupa.

Thanks to Luca Olivieri for his generous responses to my many queries and ready supply of excellent photographs for the book.

References and Further Reading

Faccenna, Domenico, and Piero Spagnesi. 2014. Buddhist Architecture in the Swat Valley, Pakistan: Stupas, Viharas, a Dwelling Unit. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications.

Olivieri, Luca M. 1996. “Notes on the Problematic Sequence of Alexander’s Itinerary in Swat. A Geo-Historical Approach.” East and West 46.1-2:45–78.

———. 2014. The Last Phases of the Urban Site of bir-Kot-Ghwandai (Barikot): The Buddhist Sites of Gumbat and Amluk-Dara (Barikot). Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications.

———. 2015. “‘Frontier Archaeology’: Sir Aurel Stein, Swat and the Indian Aornus.” South Asian Studies 31 (1): 58–70.

Olivieri, L. M. and Vidale, M. 2006. “Archaeology and Settlement History in a Test Area of the Swat Valley. Preliminary Report on the AMSV Project (1st Phase). East and West 54.1–3”73–150.

Rienjang, Wannaporn. 2012. “Aurel Stein’s Work in the North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan.” In H. Wang ed. Sir Aurel Stein: Colleagues and Collections. British Museum Research Publication 194. London: British Museum: 1–10. .

Schopen, Gregory. 2006. “The Buddhist ‘Monastery’ and the Indian Garden: Aesthetics, Assimilations, and the Siting of Monastic Establishments.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 126 (4): 487–505.

Stein, M. Aurel. 1929. On Alexander’s Track to the Indus: Personal Narrative of Explorations on the North-West Frontier of India. London: Macmillan. http://archive.org/stream/onalexanderstrac035425mbp/onalexanderstrac035425mbp_djvu.txt.

The odd thing about Buddhism in Swat, Pakistan is that it was limited to the elite Greek and Hindu rulers.

I wonder which religion the common people followed

This is my trip to Amlok Dara Stupa https://how2havefun.com/travel/amlok-dara

LikeLike