Stein Photo 28/7(3), Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

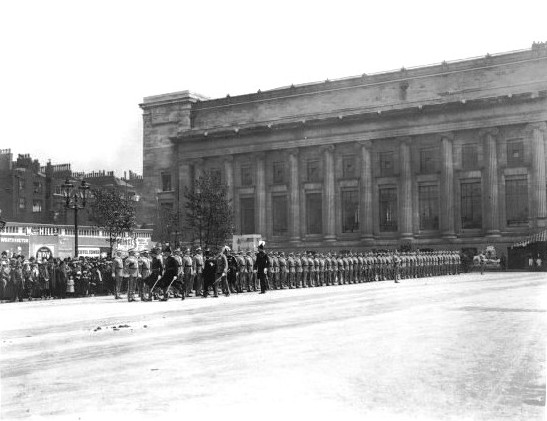

On 7 May 1914, the British Museum opened the new north wing of the Museum, the King Edward VII Galleries.1 The opening exhibition in the ground floor galleries showed paintings, manuscripts and other artefacts acquired by Aurel Stein (1862–1943) on his Second Central Asian Expedition (1906–1908).2 As noted in a previous blog post, Thomas Humphrey Ward (1845–1926), Leader Writer for The Times, considered that these were ‘the most exciting part of the display’.3 Here I look at the background to the exhibition.

In January 1909, 90 crates of artefacts from Stein’s second Central Asian expedition (1906–1908), including many paintings and manuscripts from Dunhuang, arrived in London from Bombay. Fred Andrews (1866–1957), friend and part-time assistant to Stein, was employed by the India Office Library to unpack, sort and list these. He was assisted by Mr Evelyn-White and Miss Macdonald, succeeded later by Mr Droop and Miss Florence Lorimer (1883–1967). The Museum’s share of the artefacts from Stein’s First Central Asian Expedition (1900–1901), 252 items, had been acquisitioned into the Museum’s collections in November 1911, given the prefix 1907,11. to indicate the date and some were on show.4 Andrews was thus free to work on this new material. The India Office also paid for a ‘repairer’, Mr W. J. Goodchild, to work on the paintings, supervised by Stanley Littlejohn (1876–1916), the ‘repairer and restorer’ in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum.5

In early August 1909, after fierce lobbying by Stein, the team moved from the Natural History Museum to a basement in the British Museum while Stein was on leave. As the finds were unpacked, several scholarly visitors came on private visits, including Stein’s close friend, the French scholar M Sylvain Lévi (1863–1935) in April 1910. In June that year, Andrews and Lorimer mounted a small private exhibit for other scholars. Stein noted:

‘The “private view” of the B.M. exhibition brought me into touch with some interesting & interested people, & my ancient paintings seemed to make a strong impression. A party from the Louvre invaded “nos caves” & grew quite ecstatic over certain items like the embroider picture for which M. Mignon, the “conservateur” thought we might well ask any price within the total cost of my exhibition…. Of course, I try to limit such visits as much as I can, to save our time.’6

In June 1910, 25 of the paintings from Dunhuang were included in a exhibit in the Prints and Drawing Gallery, as I have discussed previously. By July 1910 Stein notes that 70-80 banners had been flattened and by this time he had a team of 18 specialists working on various parts of the collection. This work continued throughout the following year and some of the flattened banners were displayed in the Festival of Empire in from May 1911. Stein retreated to Oxford to continue writing his account of his second expedition, Ruins of Desert Cathay. With this finished, he returned to India in November 1912 and started preparing for his Third Expedition (1913–16). Before he left he appointed the French scholar, Raphael Petrucci (1872–1917) to prepare a catalogue of the paintings.7

Stein’s second expedition (like his first) had been funded jointly by the India Office and the British Museum, with the agreement that the finds would be divided: three-fifths to go to India and two-fifths to the British Museum. Some of the divisions were fairly straightforward: for example, in 1910 it was suggested and agreed that the majority of the Tibetan manuscripts should go to the India Office Library, which already had collections and expertise in this area, whereas the majority of the Chinese manuscripts should remain in the British Museum. But others proved more problematic, especially the division of the paintings from Dunhuang.

In June 1913, the Director the British Museum, Frederic Kenyon (1863–1952) wrote to Stein raising the issue of the division and suggesting an exhibition of his work in the new galleries. Stein responded to this in July from his summer camp in Kashmir with letters to Kenyon and to the India Office. In the latter, he requested that no action be taken until his detailed report was published.8 The reply to Kenyon also discusses the division and his concerns about the lack of facilities in India to preserve the fragile material. He suggests various solutions: temporary deposit in another institution until the situation improved (and the British Museum, he adds, would be the ideal place to keep the collection together); the India Office gifting the material to this same institution; or ceding the share for monetary compensation.9 He also mentions that he is ‘happy to learn that the proposed exhibition of our collection can now be definitely hoped for by next spring’ and provides some general guidelines for the exhibition. For example, he proposes it is organised by archaeological site, with Dunhuang using the largest space. and that Petrucci is consulted about the arrangement of the paintings. Stein further suggests that the murals are positioned as close as possible to their original position on the temple wall. Andrews is left to decide the colour of the walls etc.

Fred Andrews moved back to British India in September 1913 to become Principal of the Technical Institute in Srinigar, a month after Stein had started out on his Third Expedition. Florence Lorimer was left in charge of the unpacking and listing as well as organising material for the exhibition. Stein requested a rise in her salary and for her employment to be continued until the end of 1915.10

The correspondence about the division of the collection continued, with the Government of India raising strong objections to Stein’s proposals and to his assertion that there were no museums with adequate facilities in India. They pointed out that new gallery was being built at the Museum in Lahore for temporary holding of their share, and then the finds would move into a new purpose-built museum in Delhi.11 The exhibition was proposed by the Standing Committee as a means of facilitating the division.12 It was to be held in the ground floor galleries of the new wing.

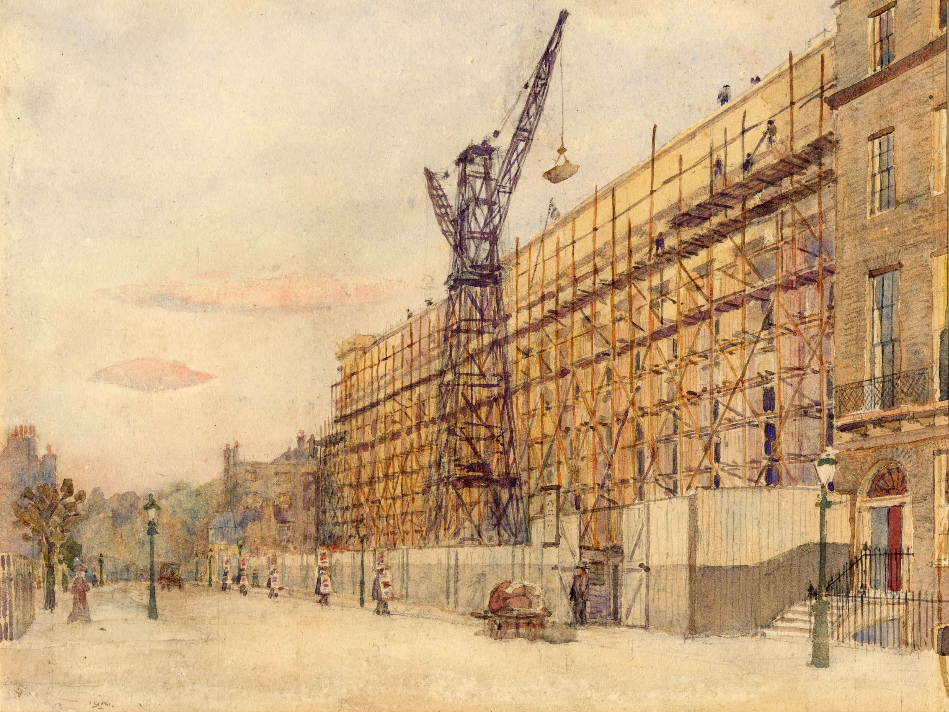

Extensions to the British Museum had been envisaged as early as 1895 when the trustees had purchased 69 houses surrounding the Museum intending to demolish them and build to the north, west and east. Work to the north finally started in 1906, the building designed by John James Burnet (1857–1938), to be knighted in 1914 for this work (Fred Andrews was, however, not impressed, describing the gallery as of ‘absurd construction’).13 King Edward VII laid the Foundation Stone (designed by Eric Gill) on 27 June 1907. However, he died in 1910 and the Edward VII Galleries were opened by King George V and Queen Mary on 7th May 1914. The other two wings were not built.

As discussed in a previous blog post, Lorimer wrote to Stein describing the opening:

‘The ceremony was very short, and the Mighty stayed in the building only for a short half-hour after, in the course of which they walked through the Gallery & Mr Binyon’s top floor Exhibition, and personally inspected Mr Dodgson, Mr Binyon, and the architect, so that you will see how much time they had to look at the exhibitions themselves. The Private View in the afternoon was most unfortunately affected by the weather; for there was a succession of heavy thunder-showers and it became extremely dark. After a time they put on the lights in the gallery but the lights at the top of the cases themselves were not yet finished, so that one could not see anything at all well; some of the India Office were at the ceremony in the morning, and also Dr van Lecoq who has just been out here for two days, and Prof. Rapson.’14

Lorimer enclosed two copies of the catalogue with her letter. Stein only received the catalogue when he was at Turfan in November 1914 and remarks to Andrews, ‘At last I got the Exhibition Catalogue, a well meant production but significantly topsy-turvy. How devoted all must be who do such work for others’ sake and anonymously!’15

Stein returned to England in May 1916 where he had chance to see the galleries. But he immediately retreated to Oxford and then, after four months there, to Devon to finish work on Serindia. He heard there of Petrucci’s early death of diptheria in February 1917 and despaired the loss of a friend but also the slow nature of research on the Second Expedition finds. He did not find England during wartime a comfortable place and decided to return to India, leaving London (via Paris) in September 1917. Before he left, he confirmed a post at Rs 500 per month for Lorimer to work with Andrews in Lahore on the Third Expedition material (although she was not to go to India until 1919).

In 1917 the division of the finds was finally agreed in London and most of the artefacts were acquisitioned into the Museum’s collections in the same year, with the prefix MAS (for Marc Aurel Stein). In 1918 Stein completed the text of Serindia at Stein’s summer retreat in Kashmir. The finds for India were packed into 67 crates and sent to the India Office in London for safekeeping during the war. The ones for the British Museum were also packed for safe keeping and in January 1919 the Dunhuang paintings were finally acquisitioned into the British Museum collections with the prefix 1919,01. The others were shipped to India. By this time, finds from Stein’s Third Expedition had arrived for sorting and the work — and discussions —began again.

*****

1 Their visit was captured by Pathe News and also reported in The Times. See Helen Wang 2002. Sir Aurel Stein the Times. London: Saffron Books: 41.

2 The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue, Guide to an Exhibition of Paintings, Manuscripts and other Archaeological Objects collected by Sir Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E., in Chinese Turkestan. (London: The Trustees of the British Museum 1914). The introduction was reproduced in a former blog post.

3 The Times, 7th May 1914, 5c; in Wang 2002: 65. He was not alone in his praise. The art historian Sir Claude Phillips (1846–1924) writing for The Daily Telegraph (7 May 1914) states that ‘they are of great novelty and importance…. ‘.

4 The finds from the First Expedition were divided between The British Museum, the India Office Library (IOL) and institutions in India. Discussion about division of the manuscripts continued up to 1917 and the India portion was only sent along with the Second Expedition finds in 1918. It was agreed that those manuscript remaining at the IOL in London were to be sent to India after their publication. After independence in 1947, the India Office was disbanded but the Library remained in London. In collections became part of the British Library in 1983. They are identified by the prefix to their Library MS. no., namely IOL or IO.

The introduction to the 1914 catalogue states: ‘‘A previous journey made by Sir Aurel Stein in 1900-1901, of which the most important proceeds are exhibited elsewhere in the museum… ’ ‘Introduction’, Guide to an Exhibition of Paintings, Manuscripts and other Archaeological Objects collected by Sir Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E., in Chinese Turkestan. (London: The Trustees of the British Museum 1914).

5 For further details of their work, and the issues arising, see my previous post,

6 Stein to Percy Allen, 19/6/10, Bodleian Library, MSS. Stein 7/64. The ’embroider picture’ is almost certainly that of ‘Sakyamuni preaching on Vulture Peak’ (MAS,0.1129) shown on display in the opening picture of this article, cat. 122 in the 1914 exhibition catalogue. Its museum reg. no, MAS,0.1129, suggests that it was acquisitioned into the collections in 1917 along with other artefacts, but before the paintings, which were acquisitioned in 1919. However, the Museum acquisition register only lists items up to MAS,0.1128.

7 Petrucci had finished two sections of this before his early death, these were published as Appendix E to Stein’s expedition report, Serindia. Laurence Binyon (1869–1943), Assistant-Keeper in charge of the Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Manuscripts at the British Museum, and his assistant, Arthur Waley (1889–1966), took over this work. A list of all the identified paintings was prepared for the end of the chapter on Dunhuang.

8 Letter to D. D. Drake, Sec. Revenue Dept. IO, 12 July, 1913. Bodleian Library MSS. Stein 10/129–31. Serindia, the report, was not to be published until 1921.

9 Stein to Kenyon, 1 July 1913, British Museum CE32/23/49. Fred Andrews reports to Stein in a letter dated 3 July 1913 (MSS. Stein 42/27-8) that Kenyon has agreed that the entire collections shoud be moved to the new wing fromt heir current home in the basements and thst Miss Lorimer will work on them there in preparation for the exhibition. He insists this opens in March 1914 or ‘not at all’.

10 To £20 per month. Letter to D. D. Drake, Sec. Revenue Dept. IO, 12 July, 1913. Bodleian Library MSS. Stein 10/129–31.

11 This correspondence is mainly found in the British Museum CE/23/32/50 to CE/23/32/108.

12 ‘In order to facilitate the eventual division of the collection between the Trustees and the India Office, the Director proposed that an exhibition be held in the Ground Floor Gallery of the New Wing in 1914.’

[Standing Committee 11 Oct. 1913/3137]

13 Andrews to Stein, 15 August 1914, Bodleian Library MSS. Stein 11/139-41. Andrews had presumably seen the galleries before his departure for Lahore. He was not alone in his opinion: Sir Claude Phillips in an article the The Daily Telegraph on the opening wrote at some length on the gallery describing it ‘a chilling environment’, most depressing’ and ‘the greatest fiasco of modern times’. See here for for a more recent assessment.

14 Miss Lorimer to Stein, this section dated 8 May 1914. Bodleian Library, MSS. Stein 94/157.

15 Stein to Andrews, 10 Nov. 1914. Bodleian Library, MSS. Stein 42/118

*********

The next post in this series will be on the 1918 Stein photographic exhibition held at the Royal Geographical Society in London.

Pingback: The Painting Left Behind | Silk Road Digressions